New York - Protesting the End of Figuration

Activism in New York from the 1950's to 2000's.

This is one of those chapters in which you start researching and writing about something, but exciting discoveries along the way eventually beget more chapters. While this material is only partial, I wanted to share it with you!

The Reality Group

In New York in the 1920’s and 30’s, there were still galleries interested in realism. In the 1930’s, a group of artists centered on the Art Students Leave and the Fourteenth Street School began renting a number of studios in Greenwich Village.

Among them was Raphael Soyer (1899-1987) and his twin brother Moses Soyer (1899-1974), both painters and printmakers who often painted workers and laborers in the neighborhood. They and many peers living in the area were “Social Realists,” a movement that flourished in many places between World Wars One and Two and was concerned with hardships of ordinary people.

By the 40’s, the movement became concerned with both domestic civil rights and the plight of war. Over the 40’s and 50’s increasing pressure in the form of anti-communist purges, coincided with a shift to abstract expressionism. Social and figurative realism lost its funding and critical attention, and became suddenly unpopular.

In 1950, Raphael Soyer invited some artist friends to a restaurant to talk about “what we believed in as painters, and of what we found wrong with the world.” About 10 artists who worked in diverse styles—including Edward Hopper—attended for the evening.

Their attempts to form a uniting credo resulted in the commitment to a belief in, and love for, “the ‘Object,’ the ‘Image.’” They described themselves as “objective painters” and felt that the “non-objective painting was a blind alley.” More importantly they felt that museums and critics had surrendered artistic values for “cults and fads, obscurity and snobbery.”

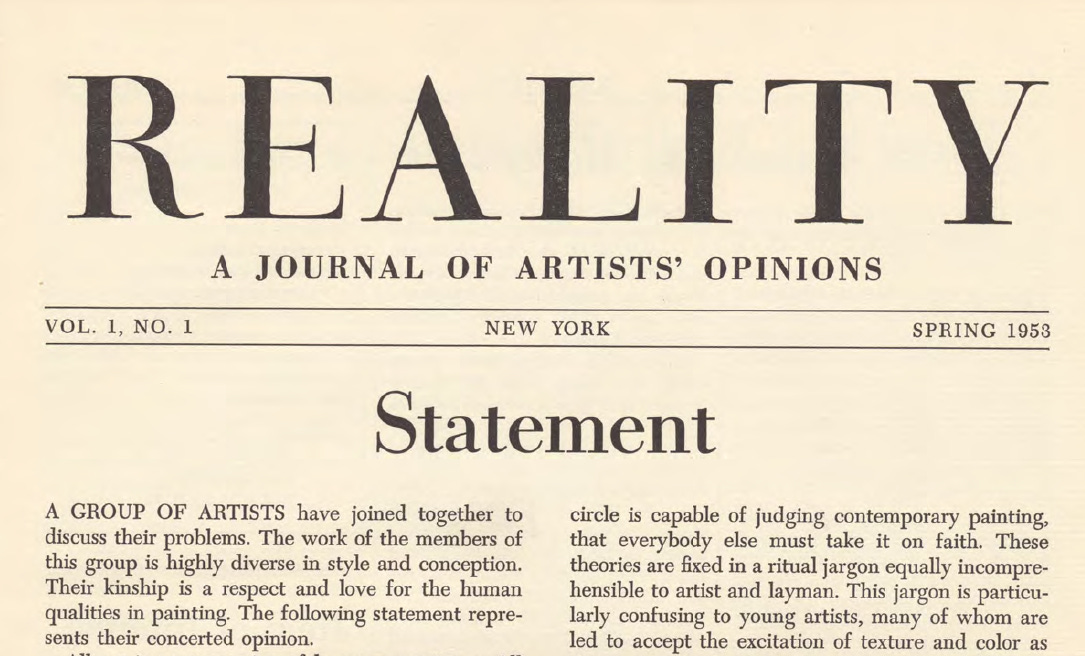

By 1953 the group had grown to 44 artists, and they formed a periodical: Reality: A Journal of Artists’ Opinions.

Apparently, Substack allows me to post PDF files! So I am posting the 1953-55 issues as well as the response from MOMA below:

The first issue featured a letter to the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA). In it, the group complained that MOMA was “coming to be more and more identified in the public eye with abstract and non-objective art.” While MOMA’s stated policy was to “oppose any attempt to make art, or any opinion about art, conform to a single point of view,” the group pointed to the “fast-spreading doctrine that non-objectivism has achieved some sort of esthetic finality that precludes all other forms of expression.”

The letter asked MOMA to give “serious and scholarly” attention on non-abstract art. In response, MOMA issued a letter that stated statistical facts proving their support of realist artists was fair, if not emphasized over the presentation of abstract work.

Yet, a shift had nonetheless occurred. Figuration ended abruptly in Europe. As European cities were filled with figurative art from the classical and early modern periods, the loss was not as keenly felt, perhaps, as in the United States. Figurative artists felt their voice was being silenced.

From Ginsburg to Assael

Abraham Ginsburg studied at the National Academy of Design in 1918-1922 and obtained a fellowship to study in Berlin and Paris. He returned to New York in the 1920’s to make a living painting portraits of famous actors for film posters. He painted one each day for four years, until he quit in 1929 to pursue his own art.

Max Ginsburg grew up watching his father Abraham paint. Max obtained a BFA at Syracuse and a Master’s at City College in 1960. By the 60’s, realism was not encouraged in school, and drawing instructors were not very good.

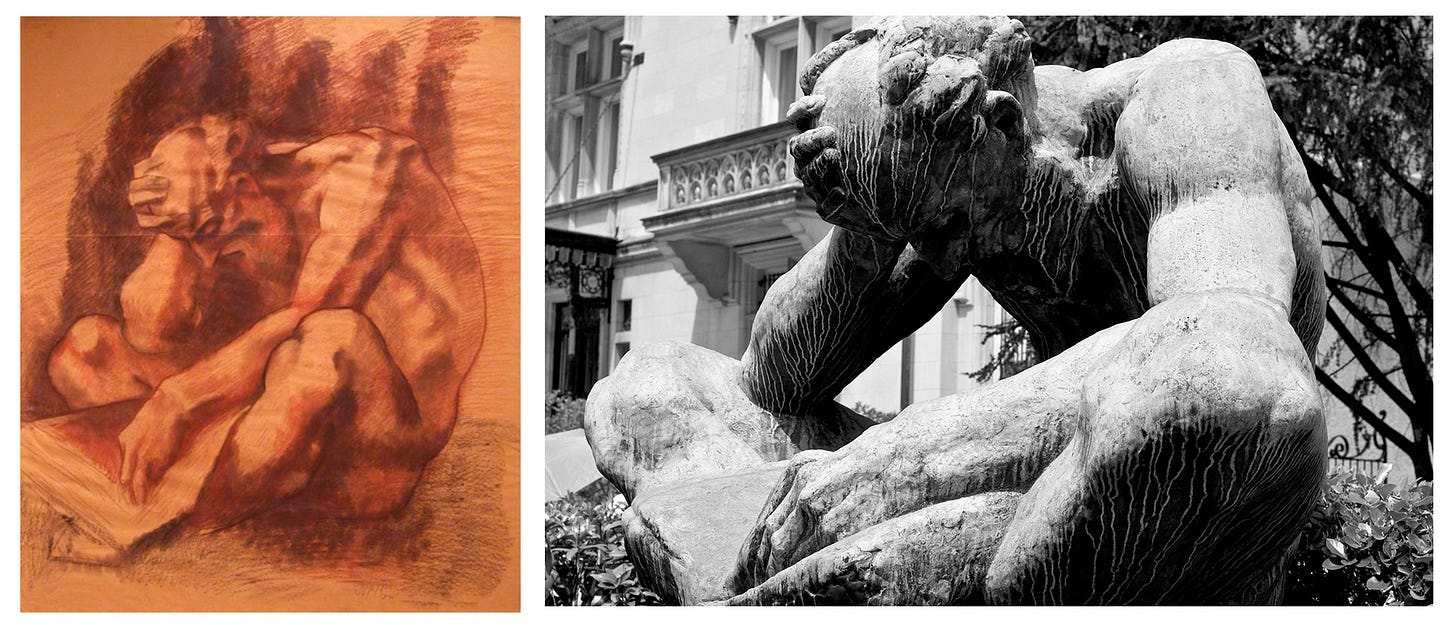

The exception was Ivan Mestrovich, a talented Croatian sculptor who only spoke Croatian and Italian, but despite the language barrier, could effectively communicate through gestures and demonstrations to enable the English-speaking students to learn the skills of anatomy and form.

In the 1960’s the Harbor Gallery on Long Island began to represent Ginsburg’s work. Most galleries preferred modernism, which allowed the work to be what Ginsberg felt was “poorly drawn;” and they would encourage him to be “more loose, less developed.” But he felt that “to distort—or not being able to see the form because your drawing is bad—is not creative. As realists we should have the freedom and opportunity to paint the reality of things.”

Ginsburg’s plan to survive as an artist was to teach part time, where he did at the High School of Art and Design from 1960-1982.

Both Ginsburg and a fellow instructor, Irwin (“Greeny”) Greenberg (1922-2009), a watercolor painter, felt that there wasn’t enough emphasis on working from life. In 1972, they started the Morning Group in which students would arrive at school to paint from a live model from 6:30-8:30 AM before beginning their regular class schedule.

It was two hours of work from life, every day of the week, for years. By the time the committed students graduated, they were good artists.

Ginsburg would pass along an adage that originated with Abraham’s instructor Charles Webster Hawthorne (1872-1930) to “paint what you see, not what you know.”

Among those in the Morning Group Steven Assael. While still a young child, Assael’s mother had taken him to classes at the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) on Saturdays for instructed drawing in the outdoor sculpture garden. He remembers drawing Rodin’s Balzac. At the age of eight, he attended a program at the Pratt on Saturdays. At twelve, he started taking classes at the Art Students League.

Later, he started at the School of Art and Design and joined Ginsburg and Greenburg’s morning program. It started at 5 AM. Sometimes, if they were painting outdoors, Steven would meet up with friends on the Subway at 3 or 4 AM in route to their location.

Assael graduated from high school in 1975 and received a full scholarship to Pratt. Although he enjoyed the liberal arts courses, the painting classes were not serious enough for the long poses required for sophisticated work, so he switched his major to drawing.

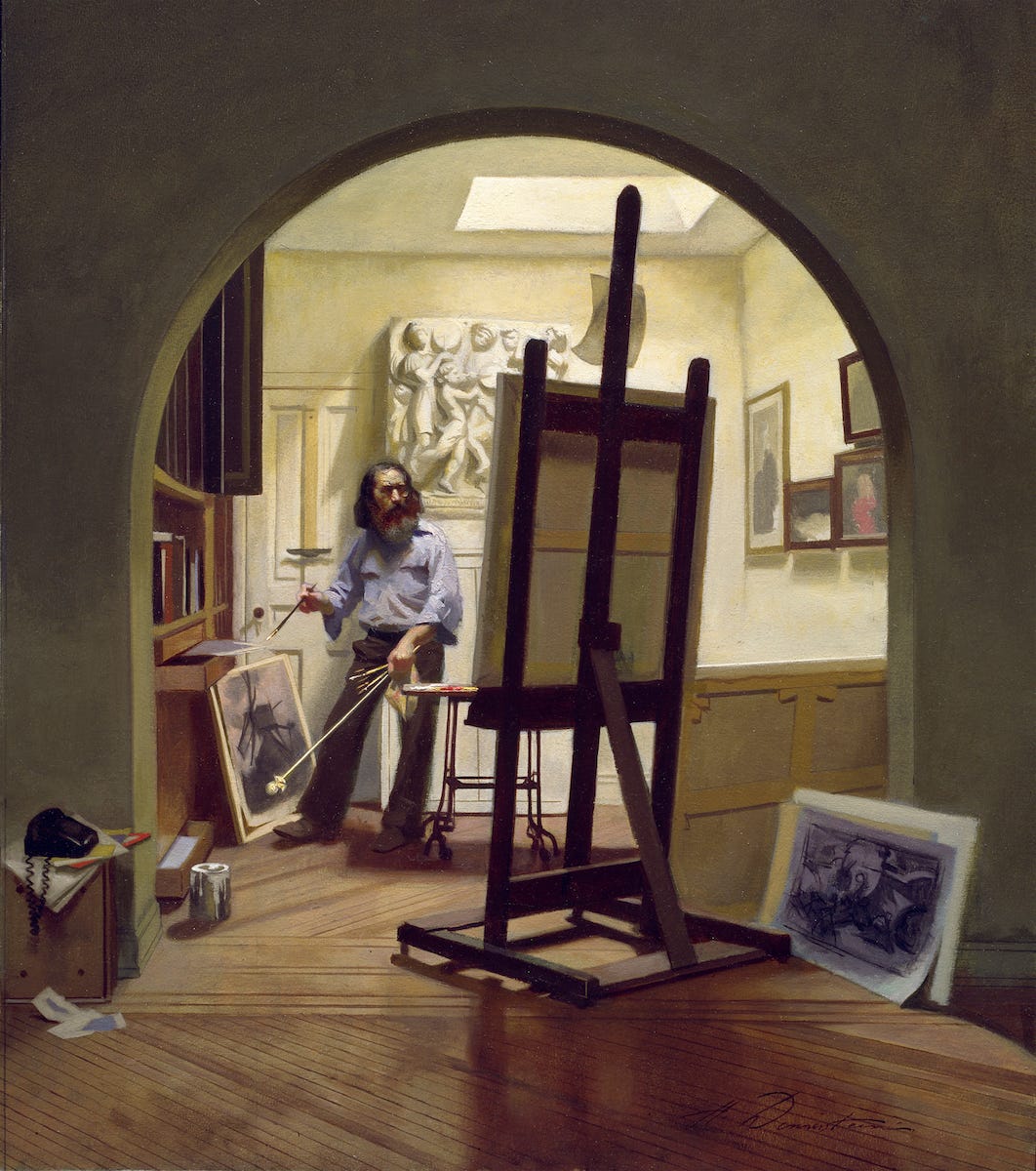

A friend who attended the School of Visual Arts (SVA), had an instructor there, Harvey Dinnerstein (1928-2022), who taught full day drawing sessions on Mondays with longer poses. Dinnerstein didn’t mind when Assael began showing up. When Assael told his friends at Pratt, the class was soon filled with more Pratt students than SVA students.

Assael and Dinnerstein would often be the last two working in the studio after everyone else had left. (They would paint together again 40 years later.)

In the mid to late 1970’s, Assael started attending the New York Figurative Alliance. It was a group of figurative artists, often social realists, who met in a loft in the SOHO neighborhood on Friday evenings. A fold-out table was set up in the loft and three people were invited to speak. Notable attendees included Jack Beale, Phillip Pearlstein, David Lavine and Jack Levine, Alice Neel, and Harvey Dinnerstein.

Meaningful conversations could devolve into intense arguments; one exciting evening involved the throwing of chairs. Some artists who attended were the first to revive techniques of 18th century academic figurative painters (“academic realism” or what is often now called “classical realism.”)

New York’s culture of social activism meant that while a student, teachers and students would take half the day off school to attend a protest in the park.

In the late 1970’s Assael took a studio where Max’s father Abraham had once held a space. To support the studio, Assael started holding classes in the space. Finances were tight; Assael would eat a 75-cent spinach pie at the Greek deli for lunch and eat dinner at the Hare Krishna temple. Devotees who were allowed to proselytize would pose as models for free.

New York Protest

On September 29, 1995, Assael and two hundred other artists gathered outside Whitney Museum of American Art. On display at the museum was an exhibition of works by Edward Hopper. Organized by phone call and fax machine, was the protest would commemorate Hopper’s involvement in the Reality group.

Two hundred protestors descended on the Whitney Museum and set up outside with a podium. The museum graciously allowed them to plug in their equipment, although event disrupted access by museum guests during part of the day.

The group was decrying the quality of the work in the museum and the categorical rejection of high-quality representational paintings by living artists.

“The only good Realist is a dead Realist in this museum” said Sigmund Abeles.[11] A placard showed a figurative sculpture by Gertude Vanderbilt Whitney and said that if she were a sculptor today, her work would be rejected by the museum.

During the protest, the speaking was paused for a “tableau vivant,” (a theatrical living picture) of a woman in classical garb holding golden scales of justice. On one side, weights labelled “Drawing, Painting and Sculpture” on the other, a much heavier weight held “Minimalist Art, Video, Installation, Photography.”

“This is a baby step,” Assael told a reporter, “of expressing our discontent.”

The next day, Whitney director David Ross faced Assael on a radio show to debate the issue on WBAI-FM 99.5. (I have been trying to track down a recording of this broadcast for months!)

The Pierre Hotel 2003

On October 5th, 2003, I flew into New York for the first time with only an address in Brooklyn scrawled on a piece of paper. Prior to smart phones, I navigated my way through the subway system and city streets to meet a speaker. I politely left. Still a student, and broke, I had expected to share a hotel room with a friend, but I never received the information on the room. My options were to sleep on park bench or pay for an hotel on credit; I chose the latter.

The next day, Michael Newberry hosted the Foundation for the Advancement of Art conference at the Pierre Hotel, in Manhattan, which stood on 5th Avenue overlooking Central Park. Planning and funding the conference was the chief goal of the foundation that I had incorporated the previous summer in Greece.

The conference was entitled “Innovation, Substance, Vision: The Future of Art” and offered talks by artists, philosophers, and vision scientists. The keynote speaker, Stephen Hicks, was a close friend and philosopher at Rockford College who had written an important critical work on postmodernism, Explaining Postmodernism.

The concept of “innovation” was key to Newberry’s vision for the organization and distinguished it from others that broadly supported artists in traditional media. The idea was to “focus on the new by recognizing those living artists that are truly advancing, through means and content, figurative, landscape, and still-life art.”

Innovation was about building upon the labors of others while transcending their limitations, “preserving what is true, discarding what is false.” In art, it might be offering original compositions or presenting themes that were applicable to modern times. Innovative artists do not copy art historical periods, but learn from the past and move forward with exciting new solutions.

“Innovation is not about newness divorced from the components that make up painting or sculpture. It is an original addition to their forms.” Newberry said.

This statement was an attack on those who felt that innovation meant exclusively using new mediums to convey art. It was also an alternative to the Stuckism movement. Newberry’s talk would highlight great art and show how it had elements that were innovative in the history of art.

Thank you for this. I was in NYC from 1983-86, trying to cut it as a realistic painter, and I found no like-minded artists. I remember going from gallery to gallery trying to get my work in, 200 galleries, but as a realist I couldn't compete with what was trendy at the time — grafitti art. If I had known of this group, I would have stayed. I went to Texas for my MFA because at least there realistic art was not forbidden. But I had to teach myself my skills and only got so far. About two years after I got my MFA, I read that there was "classical" training to be had in NYC but it was too late for me, I had student loans to pay off. I only got my "atelier" education 30 years later online, from Florence Academy and GCA people, while living in the remote Maine woods. I wish I'd known this was going on when I was in New York. I would have found a way in. I would have done anything to get these skills in my teens, in my 20s, my 30s, my 40s, my 50s, and being a realist artist alone all these decades has been rough. But I have them now in my 60s, and I am grateful that at least now it is possible to get these skills. Thanks for putting out this history. I had no idea.

I too went down there to see what was going on at the time as I had just graduated from NYAA with a masters and still am a firm believer in pursuing art as a connection to soul rather than as entertainment, momentary diversion or interior decor. I do not understand why amateurism, lack of meaning and personality cults are once again being promoted as the only acceptable forms of art. Your piece on this has confirmed that it is not new. Thankyou SO much, Brett, for your research and sharing of it. It is inspiring and reaffirming for me in these meager and difficult times.