Ch. 1: The Soul of the Artist: Michael Newberry

In which the author falls in love with art and a friendship is born.

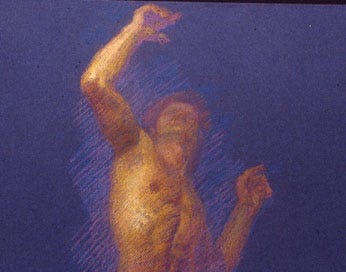

above: Michael Newberry, Male Nude

Rhodes smelled of dry grass and the sea. A steady lull of air swept quietly over the island from the Aegean.

In May of 2002, I landed at Rhodes, Greece on a puddle jumper from Athens. After completing my first year of college, I was traveling overseas for the first time to help create a cultural revolution in the arts. I was 18 years old.

Although I was a science student, I felt an emptiness as a result of knowing nothing about art. I did not draw or paint; I had never studied art history; I was, like many Americans, raised in a sterile suburb without history or culture. Art was ornament on the wall of a public library, a dentist’s office, or a hotel room. I had never watched an opera. Never been to the symphony. Never felt the space of a cathedral.

Inspired by a class in which we studied the art of ancient Greece and Rome, I had spent hours in the college library browsing giant, dusty art monographs. I covered my dorm room with posters of Renaissance works. Then, I started following contemporary artists online, gravitating toward “figurative realism,” a genre of paintings and sculpture that feature representational depictions of the world, often featuring human figures, including the nude.

Although figurative realism dominated Western art history of the classical period and since the Renaissance, it had nearly gone extinct in the 20th century, a time during which “modern” and “postmodern” art prevailed. Yet, a worldwide undercurrent of artists –from hobbyists to serious practitioners – had appeared that was unacknowledged by institutions, academia, or the press.

The internet allowed artists to share their ongoing studio work directly with the public in real time, bypassing the gatekeepers of the art press, and by 2000 the tools had become easy enough that many artists did so via personal web pages before the rise of social media. I began discovering talented artists from around the world.

When I found a sketch in pastel of a man reaching upward into the light, I fell in love with my first piece of art.

The artist was Michael Newberry, an American expat living in Greece, who painted life-sized figurative works that often featured an individual in a moment of emotional repose. Newberry’s large canvases would take years to complete, but he also performed smaller works and studies in a variety of media.

I offered to represent Newberry, and other artists, in an online art gallery dedicated to the best figurative realism. It was a small business that I could run from my dormitory in my pajamas, before classes, and would foreshadow my starting an art gallery at a physical location in Seattle, decades later.

Newberry was also an advocate for realism. Around the world, thousands of artists were emerging and sharing work with one another online, but the art elevated by contemporary museums was nonrepresentational – abstract paintings with blocks of color, performance art, or conceptual art.

Realism had zero support.

Newberry wanted to fund intellectual advocacy targeting the elite gatekeepers in the New York art world, and he needed to start a foundation to do so.

We were fast friends, and Newberry invited me to spend the summer at his studio in Greece working on the project. I had one moment of hesitation (I don’t remember why) but a friend hit me over the head and said “Are you crazy? Do it!”

On the morning I arrived, the sun was rising and filling the sky with a moving spectrum of hot color. The air was transparent, no browns subdued it, and like the feathers of some tropical bird ruffling and stretching, it moved seamlessly from yellows to reds to purples.

The landscape in Rhodes was sun-swept, tranquil; the light intense and vivid, as if objects were plucked from the world and sharpened with new tones and textures.

Driving into town, I passed around the edge of a cantilevered cliff and watched the water catch the sun and shine like molten metal. Soon the paved roads gave way to cobble stones; I passed two giant stone walls, separated by fifty yards of grass littered with cannon fire. This had been an ancient fortress, protecting the city for six centuries. Newberry had a humble home, accessed from a side alley, with a sweeping view overlooking the Old Town from a studio bejeweled with windows cantilevered out over walls of yellow stucco.

He was in his element there; he was thin, tanned, tall, with wide blue eyes and light brown hair. His laughter was giddy and free, his attitude joyful and light. He was forty-four. I remember his voice was always on the upswing, inquiring and beckoning a response.

The studio was filled with giant paintings that seemed to create their own light in the shadowy interior.

In one of them, a man stands in a waterfall, stretching upward against a flow of water that blasts against his chest and explodes in a dense vapor of light and color that rains over the rest of the scene. The expression in the face and its harmony with the lines of the nude created a sense of peace and contentment. The figure was embedded in the scene, the forms of the nude sinking into the light; to caress the surface of them with the eye was to penetrate into a private world of bliss.

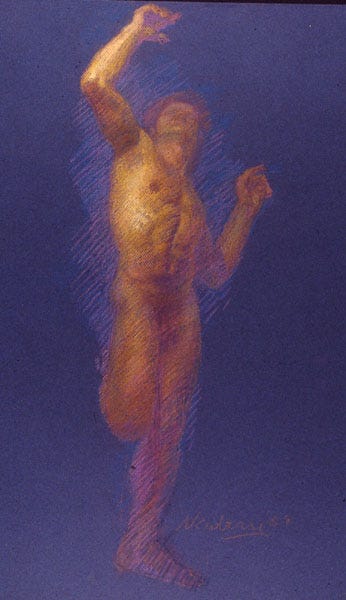

above: Michael Newberry, Synergy (and studies)

Since Newberry had been unable to find any art schools that taught the figure in the 70’s and 80’s, he had attended unstructured life-drawing sessions in Europe to learn the figure, and discovered his own technique through his early works. The benefit of this was that he wasn’t a product of “classical” art education, a rigorous style that emerged in the eighteenth century and had been taught to art students prior to the rise of modernism, which often constrained an artist’s style. Newberry invented and constantly experimented with his technique.

Some mornings, Newberry would wake and pile his pastel crayons onto the back of his moped and spend the day in the country doing vibrant studies from nature, like an impressionist, working fast to capture the light in about 45-minute intervals before the shadows changed. He would use these direct observations in pastel as color studies to inspire a vivid freshness in his oil paintings.

Without gallery representation, selling a major work rarely, Newberry had mastered the art of living well with almost nothing. There was almost no furniture in the house. It echoed with the opera of Puccini, and was filled with the scent of fresh basil and other ingredients, manipulated with Newberry’s chef-level culinary expertise.

In Rhodes there was a small community of intelligent and worldly Europeans whom Newberry befriended– advertising executives, archeologists, and others. The Greeks eat late, so dinner parties would stretch on into the cool evening.

I learned that happiness was dedicating life to the creative pursuit you loved, filling the extra time with good friends, laughter, wine, and nature. It felt to me that he lived like a billionaire, in absolute contentment, like the man in the waterfall.

It was a different life than the La Jolla wealth in which he had been raised, by socialites in a glass house near the beach and tennis club.

Newberry was trained from the age of 11 by Lester Stoffen, one of the world’s best tennis players, and competed successfully as a teenager with his older sister Janet in doubles tournaments against college players. He received a full tennis scholarship to USC.

After falling in love with Rembrandt at 12, Newberry had spent every spare moment of his teenage years, when not on the tennis court, drawing and painting, challenging himself to capture highlights and reflections. At USC, he studied fine art while playing on the NCAA championship team.

In the 1970’s, the art department at USC was dominated by “abstract expressionism.” Most professors taught classes on conceptual or found-object art. From the first weeks of his freshman year, Newberry seemed to understand that the professors at USC were not looking for skill or emotion, they were not teaching art.

He knew what art felt like; it was a universe of emotion, it was the sparkle and magic of Rembrandt. Whatever this was, was not that.

The exception in the department was Edgar Ewing. On the first day of a fundamentals of oil painting class in 1974, Ewing walked through the door in a tweed suit topped with a grizzly gray mustache and sparkling blue eyes. He set down his case on the table, spread his arms, and smiled at the classroom of freshman students.

“Making art,” he announced “is like making love.”

The students looked at one another with sidelong smiles, most of them inexperienced with one or both halves of the metaphor.

Ewing an experimental modernist painter with an infectious, childlike excitement about painting. He was an active painter who spent half the year at his studio in Athens. His style floated between realism and cubism, his colors intense, subtle, and always moving.

In Ewing’s piece Bugler’s Table, a vivid red cloth emerges from a textured cool background. Objects on the table float in various layers of transparency and shadow.

above: Edgar Ewing, the Bugler’s Table

In class, Ewing would walk around looking over the shoulders of his students. Once, while Newberry was painting a still life of bones, Ewing reached over his shoulder, thrust his thumb in the white paint, and scraped a highlight across a bone in front. Suddenly, the bone popped forward in space.

Something clicked. Newberry had spent years lovingly contemplating Rembrandt, who was a master of achieving realness of depth and space. In Rembrandt’s world of browns and golds, the gold pulled an object forward in space, and the local intensity of the contrasts between the shadows and highlights locked it into a three-dimensional space that triangulated with everything else in the painting. It produced a caressing sense of depth.

Following the insight that began with Ewing, Newberry concentrated his thought on the space of a painting, and the movement of forms through space. All the greats in history were masters of it.

Like tennis, Newberry approached his art with stamina and drive to master everything that challenged him. Each time he pushed himself, he didn’t stop until he could feel the expression and nailed it. It gave him the energy and excitement to push harder and try the next thing.

When faced with the choice of whether to be a professional athlete or an artist, he knew that in sports, he would peak in his 30’s, but as an artist, his skills would grow throughout his life, and he would be doing his best work at 80 years of age.

At USC, Newberry listened carefully to his instructors and followed their instruction. In one class, he was given five weeks to create a sculpture from premade objects and arrange them. On the morning of the day it was due, he started thinking about it. Borrowing his friend’s ranchero car, and made a bed on wheels and received a perfect grade.

After his third year, Newberry dropped the USC program. He took an offer from Holland to play tournaments in the summer, on a stipend. It would allow him to live in a small, damp studio and make art nine months out of the year. The Hague had the Royal Academy of Art, and the Free Academy, which held nine hours of figure drawing sessions with live models, three days a week.

Even one day there would be more life drawing than he had experienced in three years of class at USC.

***

Waking up in downstairs guest room of the studio, I was aware of the sound of steps back and forth across the creaky boards of the ceiling. This would go on for hours as Newberry walked up to his easel, painted a stroke, and moved back to the other side of the room to observe the effect.

Often the hallmark of a great painting is how it looks from a distance. Using distance allows the artist to check the spatial relationships in the painting, avoid getting sucked into myopic details that don’t resonate with the whole picture, and ensure forms can be seen correctly from across the room. Sometimes Newberry used a mirror to see the canvas from twice the distance of the room.

Once while watching him work, I was startled and amused to see him suddenly grab the canvas and turn it upside down. Then he walked across the room and looked at it again. A few times a month he would set aside an entire day to do this, “I will not paint today,” he said, “I will think about the painting and look at the painting.”

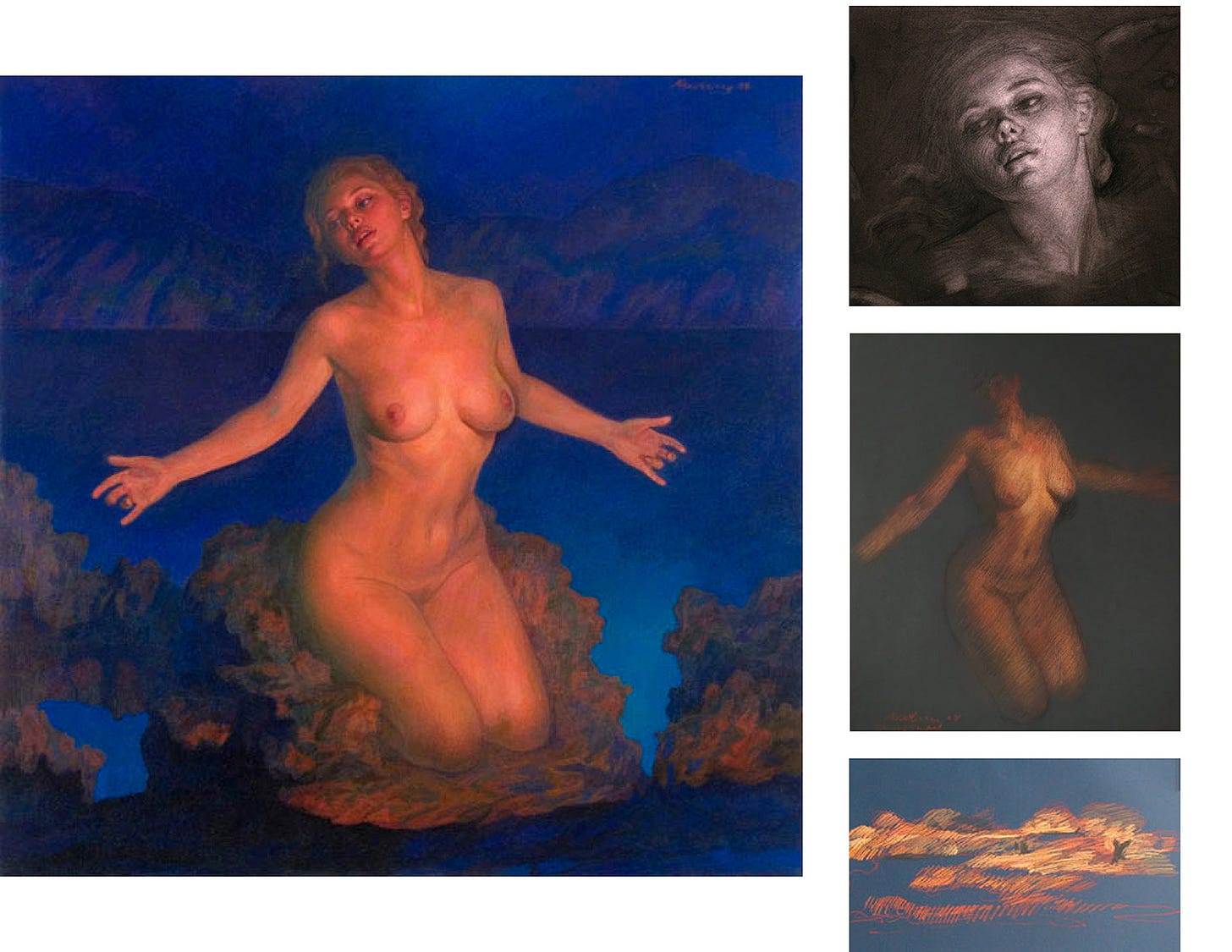

One of the paintings in process was an interpretation of the birth of Venus, a Greek myth that had been depicted by many artists including Botticelli in 1480, who placed her fully grown, standing nude on a scallop shell. Newberry placed Venus on the beach at dawn, with rocks at her feet resembling a shell, portraying a life-like scene that might have inspired the first artist to depict a seashell. The landscape behind her was the coast of Turkey, which along with the craggy outcropping of rocks was captured in pastel studies on location.

During my stay of three months, the foreground and background slowly came to life, overpainted many times. On a different schedule, Newberry painted in the figure directly from life with a beautiful friend – a tall British woman and founder of an advertising firm - posing as the model.

When finished a year or two later, the Venus radiated a golden glow; her arms are held out to either side and her head is half-turned as if to accept the caress of the sunlight on her body for the first time.

above: Michael Newberry, Venus (and studies)

Some mornings before starting work, I would rise early to walk to the beach and swim in the sea at dawn. The sun, beating down on my body, would give the wet, tanned skin a golden glow, the same caressing Venus.

Newberry’s paintings were not simply inventions of his imagination, but inspired by his surroundings, utilizing intense observation of nature. They were curated scenes that played with myth and the history of art but offered an experience universally accessible to any viewer – an internal emotional state, conveyed by the nude.

They were also a product of absolute dedication, of relentless hours in the studio and reworking the scene until the desired effect was achieved.

I would later own several studies used in the making of Venus, including a loving charcoal portrait, and a pastel study that captures the radiating light from the figure.

Our friendship never waned. Newberry’s skill would continue to improve, and by age 60, he would rely much less on overpainting to complete his major works; he had a sophisticated technique and color theory that allowed him to move from the deepest part of the background forward, every stroke of the brush in perfect resonance with the overall intention, a mastery achieved by a lifetime of effort that created a sense of effortlessness.

The themes of Newberry’s major works were not about suffering, but neither were they a shallow depiction of an unburdened life. They were genuine moments from human experience that conveyed a deep psychological depth in the subject, whether projecting the contentment of being, the radiance of emergence, or the weightlessness of great aspiration.

These themes were positive and humanistic, untouched by cynicism or fatalism, and absolutely genuine, a perfect resonance between art and life. The art, like the friendship, impacted my conception of what my life would be.

This, perhaps, is the promise of art.

***

Over twenty-five years, Newberry lived in the Netherlands, Los Angeles, New York, and finally Greece, occasionally holding shows in rented spaces while painting full time.

Although he focused his energy on large romantic figurative works, he would regularly do small pieces and perceptual studies for his larger works, including still-lifes, interiors, landscapes, and figurative sketches in pastel, oil, pencil, charcoal, sometimes experimenting with acrylic or watercolor. His smaller works were experimental poems compared to the monumental narratives of his large pieces.

In the mornings and evenings, Newberry would read philosophy and aesthetics. The rise of the internet provided access to online communities of artists and thinkers, and Newberry became more involved in discussions about the meaning of art.

Like the rest of the world, Newberry had been shaken by the terrorist attacks of September 11th, 2001. After experiencing the shock of the destruction of the World Trade Center towers, which he felt was a symbol and “expression of civilization at its height” he felt that the perpetrator had just achieved the ultimate result of the progression of art in the twentieth century, namely, the worship of nihilism that had become postmodern art.

“Postmodern art,” the series of art movements from the 1950’s on (including “pop art” and culminating with “conceptual art”) rejected of the utopian program of modernism and threw open the door to non-art mediums and objects. Art became concept; each piece was expected to participate in an intellectual discourse over what could be allowed as art. There was also a growing obsession with themes of shock, fear, formlessness, and nihilism – aesthetic ideas that could be traced back to philosophers such as Kant and Schiller. When painters still gave realistic treatment to the figure, they portrayed it with disgust.

America, embarking on a crusade to eradicate terrorism, had skeletons in its closet: it was the chief cultural exporter of postmodernism to the world. By courting a culture of nihilism at the highest level, it was courting its own destruction.

After September 11th, Newberry felt a quiet calm spread over him, and an impetus for “cold, calculating, and uncompromising action and thought.” He penned his first article, Terrorism and Postmodern Art, and thereafter would write regularly about aesthetic theory, including criticism of postmodern exhibitions and brilliant works of figurative art and sculpture.

He now had an unflinching attitude that postmodernism was intellectually bankrupt. He felt that a new art foundation, dedicated to intellectual advocacy, would be the vehicle to argue the case for the soul of the art world.

Britain was also an epicenter of postmodernism, and it had been simultaneously home grown and embraced by American museums and academia. In February of 2002, when Newberry heard that the Chairman of London’s Institute for Contemporary Arts was publicly blasting conceptual art, he boarded a plan to Britain.

I hope you enjoyed this draft of this segment from the forthcoming book: Everything is Beautiful: The revival of observation, realism, and beauty in fine art by Brett Holverstott.

Join the conversation! Your thoughts and criticisms will be valuable in subsequent drafts of this manuscript.