Ch. 2: Anti-Anti Art: Stuckism and Conceptual Art in Britain

In which the Chairman of the ICA is sacked and the Director of the Tate fails to take a hint.

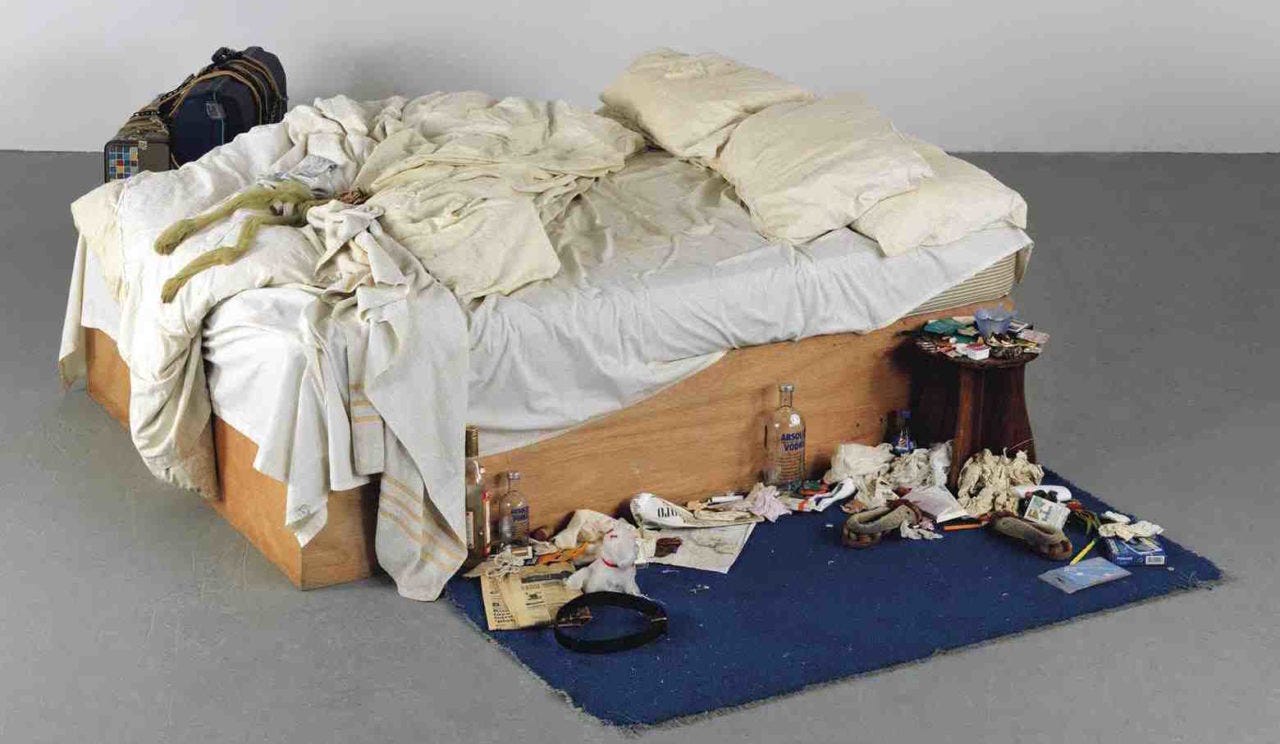

Above: Tracey Emin, My Bed

In January of 2002, Ivan Massow had an attack of conscience. The Chairman of London’s Institute for Contemporary Arts (ICA) published an editorial, without advance warning to the board, blasting the art scene in Britain, and specifically the “conceptual” art promoted by the ICA and the Tate, as “pretentious, self-indulgent, craftless tat.”[1]

Conceptual art was art in which the idea takes precedence over the crafting of a work; any object could be art if the artists gives it the significance of being so, gives it a title inspiring of thought, and places it in a gallery for refined contemplation and aesthetic appreciation. It was inspired by the historic 1917 submission of an ordinary urinal, titled Fountain and signed under the alias “R. Mutt” by Marcel Duchamp, to an art exhibition held by the Society of Independent Artists in New York, from which it was rejected.

Massow was a young, attractive, and successful gay businessman. At 23 years old he set up Britain’s first financial advisory firm aimed at gay clients. He became a financial success while crusading for gay men who had been denied mortgages and insurance amid rising HIV rates. While still in his 20’s he had flirted with politics, standing – to the surprise of the gay community – with the conservative party. He was later appointed as Chairman of the ICA in 1998 at only age 31, by a board looking to utilize his connections.

Massow’s cathartic rant Why I Hate our National Art, published in the New Statesman, accused conceptual art as having become Britain’s official art, not unlike that of a totalitarian state, supported by a cartel of which he was a part and had been, in his three years as Chairman, partly culpable. So much had been intellectually invested by the stakeholders in this art form, Massow accused, that it was now beyond criticism, and promoted without “reference to any criteria of aesthetics, originality, or intellectual challenge.” And the establishment supporting conceptual art had become “terrifyingly powerful” and “no friend to heterodoxy.”

The public castigation was shocking. The news reverberated in the press around the world. The editorial was a fun read, and pointed: Massow was attacking Brit Art as having evolved from an anti-establishment movement to the reigning orthodoxy.

The ICA was an art center that had been host to a countercultural group of artists and architects, the “Independent Group” in the 1950’s. The young members of the group were deeply resentful of the post-war establishment that English art had become, and the monopolization of aesthetic taste. The group sparred aggressively over aesthetic theory, held reading groups, and heard talks by philosophers, architects, mathematicians and sociologists.

In a cramped gallery space, the ICA held exhibitions that stimulated thinking about the future of art. The group was inspired by science and technology, the artistic products of mass communication and consumerism, and the products of American culture.

They invented a new direction for modernism – what came to be called “Pop Art,” justified with an egalitarian attitude towards any imagery produced by culture, whether a painting, jet engine, or an advertisement. The members of the group grew into governance at the ICA in the 60’s. In the 1970’s and 80’s, after moving to a larger space, the ICA was a center of London’s counterculture known for film screenings of controversial works and live performances by punk bands.

In 1989 the ICA began showing Damien Hirst and his cohort. While still a student at Goldsmiths in 1988, Hirst organized a show Freeze that attracted the attention of Charles Saatchi, the owner of a highly successful advertising firm and an art collector who would throw lavish parties from his gallery in an austere industrial space.

Saatchi showed up at another Hirst curated exhibition in 1990 and stood agape in front of Hirst’s piece A Thousand Years, before buying it. This was a large, steel and glass enclosure that featured a rotting cow’s head covered by maggots and flies, over which hung a bug zapper.

The next year, Saatchi advanced Hirst the cost to create the piece The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living, a large steel and glass enclosure holding a preserved and mounted tiger shark, which exhibited at Saatchi’s gallery in 1992.

Thereafter, Saatchi began to visit student shows, artist studios, and gallery openings, acquiring work at a rapid pace, single-handedly cementing the market for a group of artists that came to be called the “Young British Artists” (YBAs), many of whom came from Hirst’s BFA program at Goldsmiths.

Each year, the Tate – a network of four museums in the UK - elected a board to award a British artist for a recent contemporary work, called the Turner Prize. The Tate had been founded by British industrialist Henry Tate with a donation and bequest of his British 19th century works by figurative painters. The prize was named after radical British landscape painter J.M. W Turner, known for his compellingly evocative seascapes. The prize awarded £35,000 and the shortlisted artists were exhibited in one of the Tate galleries.

In 1995, Hirst was awarded the Turner Prize for his piece Mother and Child, Divided, consisting of a mother cow and a calf split in half lengthwise, with each segment preserved in formaldehyde.

Nicolas Serota, the chair of the Turner Prize jury and director of the Tate, defended Hirst’s piece: “the undoubted shock, even disgust provoked by the work is part of its appeal. Art should be transgressive. Life is not all sweet.”

In 1997, Saatchi lent his collection of work by the YBAs for the exhibition Sensation at the Royal Academy, which included 90 works by 42 YBAs and included Hirst’s shark. He fronted the two million pounds (£2M) for the installation and helped curate and install the works. The exhibit drew hundreds of thousands of visitors, shocking audiences with Marcus Harvey’s Myra, a large recreation of a mug shot of a child murderer made as a mosaic of hand prints from casts of children’s hands.

When the show moved to the Brooklyn Museum in 1999, it included Chris Ofili’s Holy Virgin Mary, the 1998 Turner Prize winner, that utilized elephant dung. This generated public protests and criticism by New York Mayor Rudi Giuliani; the shock value of the art only made it more valuable.

above: Chris Ofili, The Holy Virgin Mary

In 1999, for the first time in history, there were no painters on the short list for the Turner Prize. One of the most talked about pieces shortlisted for the Turner Prize was Tracey Emin’s My Bed.

Emin had first become infamous in 1997 when she showed up to a live broadcast panel discussion “Is Painting Dead?” in which Emin, alongside art critics and philosophers, gathered for a meaningful philosophical debate about traditional versus conceptual art. Emin was legitimately drunk, on air. Scarcely maintaining control and only semi-lucid, she chattered in the background, prompting Roger Scruton to politely ask her “will you please shut up for a moment.” She eventually excused herself to go see her mum. After her departure the fruitful conversation continued.

Her piece featured literal bed, with stained and rumpled sheets, the floor around littered with empty vodka bottles, cigarette butts, condoms, photographs, and underwear. Described by the artist as a “self-portrait, ”it recreated a moment in which Emin had a severe bout with depression after a breakup and was in bed, drinking, for four days, until finally, near death, she crawled out to get a drink of water and reflected in horror at the thought of being found dead in her apartment, surrounded by filth that had accumulated.

The first time she exhibited the work in 1998, it had a noose hanging over the bed, reflecting on her contemplation of suicide. The work was acquired by Saachi for £150,000.

In 2002, the Turner Prize was awarded to Martin Creed for an installation The Lights Going On and Off. It was an empty room where the lights went on and off.

For years, Massow had had a nagging voice in his head telling him that it was all hype.

In his article he proposed that conceptual art had become a bubble, in which “traditional artistic skill and excellence replaced by philosophical or linguistic musings, the expression of psychological trauma, or sociological comment.” And that young artists are forced to throw away their talent to become “creators of video installations, or a machine that produces foam in the middle of a room” or “piles of crap” in their aspiration to celebrity rather than artistic achievement.

Massow’s January 21st editorial was a rare and vehement act of defiance, and although he had hoped to spark debate, the piece came off as an attack on the ICA, and the situation deteriorated quickly. The ICA director Philip Dodd called for him to be sacked, giving the board a “him or me” ultimatum. As a joke, Massow sent the ICA board a toy gun so that it they could “dispatch me cleanly and humanely.”

On, February 5th, during a BBC interview, Massow heard the news that the board had unanimously agreed to ask him to resign.

After the interview, Mick Jagger, who liked what he had been hearing on the air, pulled up in a limo and took him to a party, where Nicholas Serota was present.

“I’ve been fired.” Massow told Serota.

“About time, too.” Said Serota, turned around and walked off.

The Stuckists

In January of 1999, Charles Thomson and Billy Childish started a group of painters, the “Stuckists,” that would become a countercultural reaction to conceptual art in Britain.

Thomson, an artist and photographer, and Childish, a garage punk musician, had both started painting again after a long absence, during which their friendship waned. Years before, they had been part of a punk poetry performance group, the Medway Poets, who from 1979 on could be found at pubs, colleges, and festivals, reciting poetry with whisky bottle in hand, and sometimes spraying it on those sitting too near the poet. After running into each other after a screening of Wayne’s World in 1999, the two would be joined by several other members of the former group.

The name was inspired by a poem that Childish had written in 1991, which recounted words by Tracey Emin–his girlfriend at the time – who claimed “that he was ‘stuck’ with his art, poetry and music” and reinforced it by adding “stuck! stuck! stuck!” Emin, in the years since, had ceased painting and become a popular conceptual artist, but had spent years in Childish’s punk social group. As numerous historical movements, including impressionism and expressionism, had been named by their critics, Thomson felt that “Stuckism” would be appropriate for the new group.

Stuckism was deep in manifestos. Although Stuckists were artists, musicians, poets, writers, and photographers, foremost among its values was a commitment to painting, a medium that is “adaptable” allowing “precise and subtly evocative communication” with an “enduring capability […] to communicate and evoke” whereas conceptual art was about the medium itself, a choice that could only convey meaning once.

Stuckism also placed a high value on “profundity of meaning,” “emotional veracity” and “authenticity and honesty of the creative impetus” whereas conceptual art was about “novelty on the surface and nihilism deeper down” in which “irony and game-playing” substituted for “self-knowledge.”

It also called for art that was holistic, that would be “alive with all aspects of human experience” and “create worlds within worlds, giving access to the unseen psychological realities we inhabit” rather than the “story of fragmentation” of modernism, in which each movement was “part of a static uncompleted whole.”

The Stuckist manifesto called for a quest for authenticity and meaning in traditional media, but did not call out an aspirational visual style aside from representational figuration.

The artwork created by Stuckists was eclectic, and sometimes a rehash of modern and postmodern styles including expressionism and pop-influenced art, often admittedly “clumsy” and particularly in Thomson’s case, referential.

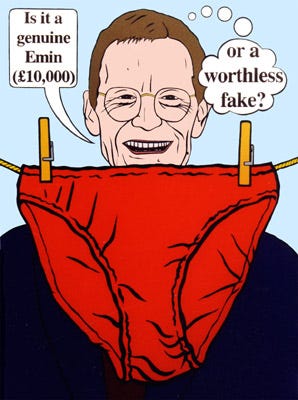

The most talked about piece was Thomson’s Sir Nicholas Serota Makes an Acquisitions Decision in which Serota, director of the Tate, is shown holding admiring Tracey Emin’s knickers hanging on a washing line, asking “Is it a genuine Emin or a worthless fake?” which after creating in the day before the show, Thomson exhibited alongside work by other Stuckists in an exhibition titled “The Resignation of Sir Nicholas Serota” that took place in March of 2000. (Serota had not resigned, as the exhibition title suggested, nor did he take the hint.)

Above: Charles Thomson, Sir Nicholas Serota Makes an Acquisitions Decision

The group, with a punk attitude, would be a standing annoyance to the art world in Britain, and particularly Serota, whom Childish and Thomson singled out with an open letter in 2000, to which they received no reply.

In October of 2000, Stuckists hosted another exhibition, the “Real Turner Prize Show.” In November, they dressed up as clowns at the Tate exhibition of the Turner prize finalists, in protest, to make the point that “the Tate had been turned into a circus” and they were featured in an article by the Guardian covering of the winner of the Turner Prize. They repeated the protest for the next two years; on the third, they arrived with blow-up sex dolls.

In 2002, Stuckists, again dressed as clowns, carried a coffin marked “The death of conceptual art” down Charlotte Road and set it down in Hoxton Square outside the White Cube Gallery, which represented Emin and Hirst.

Stuckism acquired members rapidly and Stuckist groups began to appear all over Britain and the world. Guerrilla tactics were part of the group’s punk activism culture. After Cornelia Parker received permission by Tate Britain to wrap Rodin’s sculpture The Kiss in a mile of string, Piers Butler, founder of a Stuckist group in Notting Hill, walked in with scissors and cut it off, restoring the work to its original beauty.

In 2005, Thomson offered to donate 175 Stuckist paintings to the Tate. Serota replied with a letter that said the work was not “of sufficient quality in terms of accomplishment, innovation, or originality of thought to warrant preservation in the national collection.”

Inspired to research Tate’s acquisitions policy, Thomson began to uncover the names of trustees, and with a Freedom of Information Act request, uncovered that Tate had recently purchased, for £705,000, the piece The Upper Room by Chris Ofili, while Ofili was serving on the board of trustees. It was an ethics scandal for Serota, and forced Tate to apologize for using a £75,000 grant from the National Art Collection to help fund the acquisition.

The Stuckist movement succeeded in getting media attention, harassing the conceptual art world, and criticizing the Turner Prize as “an ongoing national joke” in which “the only artist who would not be in danger of winning [..] is Turner himself.”

It also helped normalize the views that would facilitate prominent individuals to speak out. After Ivan Massow’s media-storm editorial in February of 2002, in December, Kim Howells, UK Culture Minister, after seeing the entries for the Turner Prize, pegged a comment card to the wall at the Tate Britain:

“If this is the best British artists can produce then British art is lost. It is cold, mechanical, conceptual bullshit.”

But is it Art?

In the 1997 panel discussion “What is Painting” notable critic Waldemar Januszczak voiced that he was certain that painting’s reign is over, because of the “absolute inevitability and breath of the media revolution.” Although he loved and adored painting and owned several paintings, he was against the idea of painting as the only way of making art. Cast this way, painting was a monopoly to be overcome, not a cultural tradition suppressed almost to extinction by conceptual art.

In their manifesto, Stuckists claimed “if you are not painting you are not an artist.” It was an over-simplification for effect, as many Stuckists were artists of various artistic genres, but was directed at conceptual art.

Thomson argued against conceptual art: In normal circumstances, an everyday object is merely itself. But if we are to accept the premise of conceptual art, when an everyday object is placed in a gallery, it ceases to be merely itself and become worthy of appreciation as art. Yet, if any object in the world can be perceived as art in a gallery, then it could likewise be perceived as art under normal circumstances. Therefore, the gallery is frivolous, and “the logical progression of art into life will have been fully realized and the need for art completely extinguished.”

In short, if anything can be art, then nothing is art.

Yet the conceptual artist transforms an ordinary object into art in the same way that Thomson feels is necessary for the creation of a traditional artwork: an intention, a “consciousness of profundity and meaning to generate it.” Works by Hirst and Emin are both written about for the ideas they seem to represent.

However, Thomson argues that conceptual art lacks the appropriate means for the intellectual expression. The artwork, for a conceptual artist, is the idea itself, almost divorced from an object that has any value. The object can be replaced or remade without any loss to the artwork. There is no requirement for craft.

A conceptual artwork may communicate, and arguably the most convincing to the public are those that seem to spontaneously generate meaning in the minds of visitors. But the artwork does not need to do so natively; the meaning can be attached in the artist’s statement, or the artist’s statement can be disembodied, without a corresponding work. If the object were not sitting in a gallery or similar environment, it would not be clear that it is intended to communicate anything. Whereas, a painting, by being a painting, conveys to the observer that it is offering an experience, and the content native to the work itself.

Perhaps the most insufferable conceptual art is work in which neither the object itself has value, nor does the idea have any meaningful content. Like a celebrity famous for being famous, the work is simply the first instantiation of itself.

The piece Comedian by Maurizio Cattelan is a banana taped to a wall; it has no meaning or idea, but once manifested in the mind and proposed as an art object, is a seminal event that cannot be repeated without loss of originality. This is, quite literally, originality for its own sake.

But an artwork is not merely a vehicle of communication, it can create a powerful emotional experience in our mind. Since the 1830’s, when the idea of “art” split most conclusively from “craft,” the West has sought an “aesthetic pleasure,” one associated by various writers with spirituality, beauty, moral instruction, truth, and the creative imagination. When confronted with an artwork that presents a coherent vision, we are faced with a “possible world” to inhabit (according to Leibniz) one that can create in us a feeling of the sublime.

An intellectual argument against conceptual art is, like a conceptual art piece itself, an art movement disembodied. Stuckism failed to deliver on their lofty promise of paintings invested with meaning and authenticity.

In retrospect, there are several ways they could have done so. They could have presented excellent curated exhibitions of impactful works that emotionally resonated with the public. They could have written important pieces of criticism highlighting the very best from Stuckists or artists from around the world, and actively sought to exhibit works that fully embodied their promise.

This would have required a cultural value missing from the Stuckist manifesto: the elevation of excellence. To maintain this would have required formulating how to evaluate excellence, such as technical innovation in the context of the history of art, and how the craft is utilized to serve the values of meaning and authenticity.

Instead, Stuckists were entrenched in the culture war of the present. They stood against an art trend that was, they felt, anti-art. But it was never viscerally, visually clear what they were for.

They were anti-anti-art.

I hope you enjoyed this segment from the forthcoming book: Everything is Beautiful: The revival of observation, realism, and beauty in fine art by Brett Holverstott.

Join the conversation! Your thoughts and criticisms will be valuable in subsequent drafts of this manuscript.